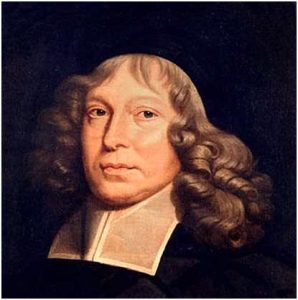

Although Samuel Rutherford died 350 years ago and not many will have heard of him outside Scotland, they may know about his letters for which he was famous. However, as we shall soon see, Samuel Rutherford had a much larger contribution to make to the Christian cause, particularly to his native Scotland but also to the whole country and the world at large.

Well, Faith Cook in her book “Samuel Rutherford and his friends”, says “Over 350 years have passed since the small fair-haired pastor of Anwoth took up his pen, and in his scarcely legible hand began to write letters to the scattered members of his congregation and to his friends. And yet the letters still live on, flowing straight from his own deep experience of the Son of God. Rutherford’s words moved, challenged and consoled the hearts of those to whom he wrote. They were read and re-read then carefully treasured up and at last in 1664, three years after his death, were gathered up together and published for the first time.” There were 365 of them.

Humble Beginnings

Samuel Rutherford was born in 1600 in the parish of Nisbet in the county of Roxburgh about 4 miles from the town of Jedburgh which is just inside the boundary of Scotland in what is now called the Borders Region of Scotland.

Not a great deal is known of his early years, his father was a respectable farmer, and Samuel had 2 brothers, George and James. They were all sent to a school in nearby Jedburgh abbey. When Samuel was about 4 he had a very dramatic experience. When he was playing with friends on the village green, he fell into the village well. His friends ran to get help and when they arrived they found a very wet Samuel sitting on the grass. When they asked how he got out, he just said – “A bonny white man came and drew me out of the well” – No one was ever to find out who this bonny white man was, but by God’s providence Samuel’s life was spared.

Samuel Rutherford – Scholar

He appears to have done well at school, and in 1617 he went to the University of Edinburgh, where he studied classics, philosophy and physics for 4 years. He graduated with a Master of Arts Degree, and 2 years later in 1623 he was appointed the Professor of Latin language and Literature at the University, and was called the Regent of Humanities. His primary duties included teaching Latin and Greek and lecturing on Roman literature.

As is so often the case when reading biographies by different authors concerning men like Samuel Rutherford, it is very unclear as to when he became a Christian. Some say it was in 1624, but Andrew Bonar suggests that it was not until 1626. It is clear though that he suddenly came to a clear and saving faith in Christ. He said – “O but Christ hath a saving eye. When He first looked on me I was saved, It cost Him but a look to make hell quit to me”.

After Samuel Rutherford began his university teaching he married Eupham Hamilton. Soon however a scandal arose in connection with this marriage and it is very unclear from the biographers who have studied the University records what exactly transpired. It is thought that some in the University and Church hierarchy in Edinburgh did not like what he was saying and his power of influence in the University. They used his marriage to Eupham and the scandalous reports to get rid of Samuel. Whatever the facts were, Rutherford resigned his professorship under a cloud.

Whether this disturbed his conscience or not, it is clear that for the rest of his life, he remembered with regret and repentance the sins of his younger years. He was to write – “The old ashes of the sins of my youth are a new fire of sorrow to me”.

Samuel was, as we have already seen a great thinker and during his final years teaching at the University, he also studied theology and prepared for the ministry.

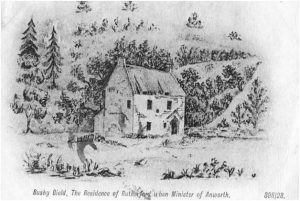

And So to Anwoth

When Rutherford completed his theological studies in 1627 he responded to an invitation from Sir John Gordon of Lochinvar to come to pastor the church in the parish of Anwoth in Galloway and Rutherford was to be its first pastor.

As Rutherford commenced the pastorate that was to last 9 years he said, “I have received the commission from the royal and princely Master my Lord Jesus to preach Christ to the people”. His was the passionate desire of the true pastor for his people’s conversion and his records say that he seemed to be always praying, always preaching, always visiting the sick, always catechising, always writing or studying. As Faith Cook says in her book “when he walked it was observed that he held his face upwards” – what a wonderful description of a pastor.

He was greatly concerned for the responsibility he had been given for his flock at Anwoth.The congregation was a widely scattered one and Rutherford must have spent hours trudging along upland tracks to visit his people in their isolated farms and cottages.

It is very evident from looking at some of his letters (many of which were written to his congregation) that he had gained an intimate knowledge of the family circumstances and spiritual needs of those for whom he had a responsibility.

Many of his letters and sermons were rich in references to rural life, and these long walks he used to take must have given him much of the graphic imagery that he drew from the world of nature.

During those early days at Anwoth, Samuel Rutherford found that the work of the reformation in the previous century had left its mark. John Welsh, John Knox’s son-in-law had been the minister in Kirkcudbright 25 years earlier, this was just down the road, and there were still other faithful ministers then, scattered here and there over Galloway and Ayrshire who were in agreement with Rutherford in his theological and ecclesiastical principles, and he held up high the banner of the reformation.

Samuel Rutherford – His Character & Devotion

Rutherford’s letters show that he was a very thoughtful man. It has been observed that during this period of his life, tenderness was one of his most characteristic qualities. He was also powerful in his handling of practical subjects and denouncing the prevalent vices of the day. In his preaching he had a power to arrest and captivates the people’s attention.

Rutherford spent a lot of time in his personal devotions with his God, he used to get up every morning at 3am for Bible reading, meditation and prayer. He had a special hallowed spot midway between the manse and the church among the trees, which was caIled Rutherford’s Walk, where he used to go for prolonged devout thought and prayer.

After a while attendance at the Church grew. From many parishes, far remote to Anwoth and without a faithful ministry, multitudes flocked to hear Rutherford, hungering for the teaching of heavenly truth.

A very intriguing incident is recorded by all the writers on Samuel Rutherford, this was a visit from an Archbishop. The actual date is uncertain but seems to have been early on in his ministry at Anwoth, when Archbishop Usher was on his way from England to his diocese in Armagh. Passing by Anwoth on the road to Portpatrick and the boat to Ireland one Saturday afternoon, he was anxious to hear the preaching of Rutherford, whose fame had obviously spread far. The Archbishop assumed the disguise of a wayfaring man and turned up at the manse asking for a lodging for the night.

As good pastors are not to be forgetful to entertain strangers, he was received readily. It was the practice of Mrs Rutherford while her husband was preparing for the coming Lords Day to gather together her servants and the strangers within her house for catechizing, and on this occasion the stranger in lowly garb joined the little group. To test the knowledge of the wayfarer she asked him how many commandments there were to which he answered 11. Later in the evening she told her husband about the wayfarer and the answer given with her fears that the stranger was not well instructed in religion.

When Rutherford got up early at 3 in the morning for his private devotions in his usual place, he was astonished to find that someone had got there before him, and even more surprised to discover that it was the stranger deep in prayer.

After a time of prayer Rutherford accosted him and told him that he didn’t think he was who he seemed to be. Usher then revealed who he was and they spent the next few hours talking about their religious experiences, remarkable as it was Usher was not averse to conform to the simple form of Presbyterian worship. Rutherford asked him to preach that morning at the church at Anwoth, whereupon he preached on the text “A new commandment I give unto you that you love one another”. Furthermore the Archbishop decided to delay his journey for another day, so that he could spend more time in spiritual conversation with Rutherford.

Samuel Rutherford was to experience many personal trials during his days at Anwoth, both his children died in infancy, and in 1630 his young wife Eupham died after suffering for 13 months from a distressing and lingering disease.

One of his most faithful friends at Anwoth was a lady called Marion M’Naught, she was to become one of his principle correspondents, of whom he wrote – “Blessed be the Lord, that in God’s mercy I found in this country such a woman to whom Jesus is dearer than her own heart “. The earliest letter to survive from Rutherford’s pen was written to her. She was married to the Provost of Kirkudbright, and it is clear from the writings that at all opportunities she would be found listening under his ministry.

When Rutherford’s wife Eupham was dying she sent her daughter Grizzell to look after them, and after she died Rutherford was himself ill and for 3 months was unable to preach. Again Marion M’Naught despatched her daughter to look after him until he was fit and well.

Troubles – From Anwoth to Exile

Samuel Rutherford was living in troubled days for the true Church of Jesus Christ. The Reformation in the previous century under such men as Knox had restored the Word of God to its rightful pre-eminence, and the un-Biblical church practices had been replaced by Biblical ones.

It was not therefore very surprising that Rutherford’s ministry following, as it did the same biblical mould as Knox, was closely watched by those bishops and clergy anxious to bring the Church back to pre-reformation forms. The influence of a man of Rutherford’s ability could not be confined to a quiet country parish in deepest Galoway, He was in close touch with other prominent reformed church leaders in Edinburgh and throughout Scotland who were opposed to the introduction of changes in the manner of worship that were the mere traditions of men. He had joined with them in their public outcry against these evils and condemned the divergence from the true doctrine of the Reformed Church.

To this end he wrote a book in Latin in 1634, the title of which was “Exercitationes Apologeticae pro Divine Gratia” this exposed with devastating clarity the errors of Arminianism and Archbishop Laud the Archbishop of Canterbury.

These bishops now had great power over what could and couldn’t be preached, and they were able to institute a High Commission Court composed of the Bishop and a few like minded clergymen whom he had the exclusive right to nominate. As this court had the power to imprison or otherwise punish all within their jurisdiction who resisted their authority, it is easy to see how terrible oppression to the true gospel was looming fast.

When Samuel Rutherford started in Anwoth the local Bishop of Galloway was a Bishop Lamb, who was tolerant of Rutherford’s theological position; however he died and was replaced by a man called Thomas Sydserff who was the Bishop of Brechin.

Sydserff was an ardent Arminian, and in 1634 Rutherford’s work came to his attention, his fate was sealed. He was ordered to appear at the ecclesiastical court in Wigtown. His punishment was that immediately he be deprived of his ministerial office, however not satisfied with this, Sydserff ordered that he must appear before the High Commission Court at Edinburgh and that he should be charged not only with nonconformity but with treason against the King.

Three days were spent in this trial over pointless questions. When Rutherford spoke in his own defence it became evident that some of the other commissioners had been moved by his statements and were going to acquit him, but Bishop Sydserff became very angry and with oaths declared that if the court didn’t find him guilty he would take this to the King, the threats worked and Samuel was found guilty, he had already lost his church in Anwoth, now he was to be banished to Aberdeen

So began his period of exile. For the next 22 months, he was to live in a room at No. 44 Upper Kirkgate, in Aberdeen, away from home and friends, forbidden to preach in public by his enemies.

Although he did suffer from periods of depression and a feeling of uselessness during this time, above all it was what he called the dumb or silent Sabbaths that distressed him most, remembering his flock left behind at Anwoth like the sheep without a shepherd.

He used his time there however to great effect; his letter writing began in earnest, out of the 365 letters written during his lifetime, 220 were penned during his exile and imprisonment in Aberdeen. He wrote from what he called “my kings palace”.

As has already been said a large number of letters was sent to his friend Marion M’Naught, many were also sent to Lady Jane Kenmure the wife of Sir John Gordon later Viscount Kemmure the local lord, other letters were drawn out by the sorrows and bereavements that befell some of his parishioners during his absence while others were sent to rebuke backsliders, to arrest young men who were in danger of being led astray, and to warn those who were showing tendencies to defect away from the truth.

When he arrived in Aberdeen, the Bishop of Aberdeen and some of the clergy engaged in meetings challenging the solitary stranger to a dispute on the Arminian points of view and innovations in worship. On the third meeting their principle spokesman, a Dr Barron, received so many hard knocks that they gave the banished minister a wide berth from then on. Maybe this is a challenge for our day to keep standing for the truth in doctrine and practice. Folk like those at the Christian Institute may one day be able to silence the opposition.

After a short while however the influence of Rutherford began to be felt in Aberdeen among the people. Although forbidden to preach he had a number of good personal contacts. In one of his letters he wrote – “There are some blossomings of Christ’s kingdom here in this town, and the smoke is rising and the ministers are raging, but I like a rumbling and roaring devil best” – When this came to the attention of the bishop and his clergy they were filled with alarm as this was just the kind of thing they wished to avoid, they threatened Rutherford’s contacts and also considered banishing Rutherford to Caithness, the Orkney Isles or even outside the kingdom.

Events were however taking place elsewhere in Scotland that would have a significant effect on Rutherford.

Tensions in Church & State

It is true to say that over the next 25 years, these three were to cause Rutherford and the church in Scotland many troubles.

During those 22 months of confinement the tension between church and state was steadily rising. King Charles 1st with his problems already in England needed to control the activities of the Scottish Church. His strategy lay in strengthening the Episcopal system at the expense of Presbyterianism, and this was masterminded by Archbishop Laud as we have already seen.

In 1637 Charles tried to enforce the Five Articles of Perth introduced by his father James 1st. These sought to bring many practices into Church worship strongly reminiscent of pre-reformation days. This was followed by the enforced introduction of a new Book of Common Prayer compiled by Laud, but apparently borrowed word for word from the Roman Mass Book.

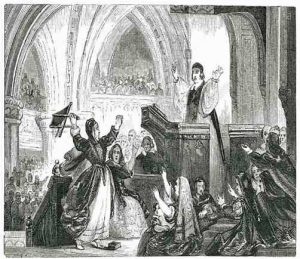

There then followed the well publicised event on Sunday, JuIy 23rd 1637 when Charles ordered that this Prayer Book must be used in all the Churches in Scotland.

The atmosphere was already charged with tension when the Dean of Edinburgh, a James Hannay, arrayed in his new robes, stood up in St Giles Church in Edinburgh in the place where Knox used to preach, to conduct worship from this new book, when a lady in the congregation, a poor green grocer called Jenny Geddes stood up and threw her stool at the Dean just missing his head, she then uttered the famous words – “Rascal wilt thou say mass at my lug”.

This incident sparked off what Scottish Historians have delighted to call the Second Reformation

It was necessary to guide this rising tide of public feeling in the right direction, so the Scottish Privy Council sympathising with this popular enthusiasm sanctioned the appointment of a Special Commission called “The Tables”

The National Covenant

The outcome of all this was to be the renewal of the National Covenant of Scotland, in which the people should – QUOTE – “Bind themselves to adhere to and defend true religion and forbearing the practice of all innovations already introduced into the worship of God, to labour by all lawful means to recover the purity and liberty of the gospel as it had been professed and established before the aforesaid innovations”.

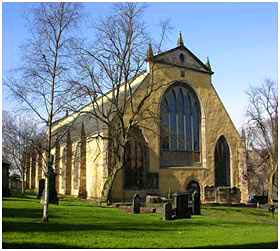

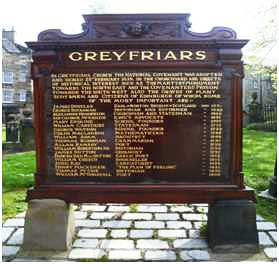

This culminated in one of the most famous and momentous events in Scotland’s history, the public signing, acceptance and adoption of the National Covenant that took place on March 1st 1638 in the Old Greyfriars Church in Edinburgh.The occasion is well documented, when all within the church had signed the covenant, it was taken outside into the churchyard for the thousands of others who wanted to add their names to the growing register of the covenanted host, some even subscribed with their blood or wrote after their names “until death”.

Many people have written much about this event, it has been described in terms of a Pentecost and a second reformation. Whatever it was or wasn’t it gripped the nation and the people were aroused by a great zeal unfelt since the time of Knox.

It is very unclear as to where Rutherford was when this event took place, each writer says something different, Rutherford left Aberdeen of his own accord during 1638, Some think that he was present in Edinburgh for the signing of the Covenant on March 1st, other writers report that Rutherford apparently back in Anwoth hurried to Edinburgh and was one of the first to sign, paintings of the scene do show him at the signing.

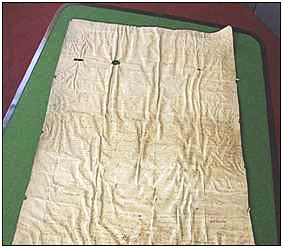

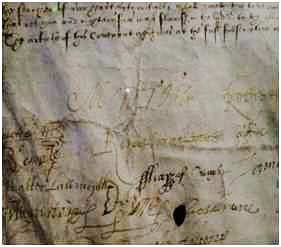

However it is apparent that Rutherford did not leave Aberdeen until June as his last letter was dated from Aberdeen on June 11th. Robert Bailles in his Letters and Journals states that Rutherford preached in Glasgow in June on his way to back to Anwoth. Andrew Stevenson in his 3 volume work “History of State and Church in Scotland” 1625-1649 “ records all the Ministers who signed, and Rutherford’s name is conspicuously absent. The most conclusive evidence however which Faith Cook reports is that a careful study of the original Covenant, now yellowed and worn is preserved in a museum in Edinburgh, 4000 Signatures have been counted but none appears to be Rutherford’s.

Nevertheless, Rutherford would have been in wholesale agreement with the covenant, whether or not he actually signed it. He was now back in his beloved Anwoth preaching the gospel again after an absence of nearly 2 years.

Rutherford – A College Professor

But it was not for long, Rutherford’s gifts could no longer be confined to a small parish in Galloway, The General assembly of the Church of Scotland suggested that he be appointed the Professor of Divinity at St Mary’s College in St Andrews.

Rutherford was not keen to go at first., His congregation at Anwoth were filled with dismay, and the whole Galloway area united in sending petitions to have the appointment revoked.

Rutherford had to go, The one condition he asked for and was given, was he wanted in addition to his university duties to be able to preach regularly at St. Andrews.

It was with much sadness that Rutherford left Anwoth in October 1639 for St Andrews. In a letter to Lady Kenmore he writes – “My removal from my flock is so heavy to me, that it maketh my life a burden to me, I had never such a longing for death, The Lord help and hold up this sad clay”.

Later that month Rutherford was inducted as co-pastor at St Andrews Church and worked there for the next 3 years.

Scarcely any records of his work at the University were preserved; it is known that in addition to lecturing on Systematic Theology, part of his work was to instruct his students in the Hebrew language and Church History.

After 5 months at St Andrews, having been a widower for nearly 10 years he married Jean McMath. An early biographer writes of her – “A person of great worth and piety, worthy of such a husband”.

If the 1630’s were difficult years for Scotland they were to get worse, While Rutherford was working at the University many events were taking place around him.

King Charles 1st annoyed at the rebuff he had received north of the Border and unable to convince the Scots, decided that force would be the only way. As Charles prepared for war, the Scots put their forces under General Alexander Lesley and his brother David. In the two battles that followed first at Berwick and then more decisively at Newburn on Tyne the Royalists were routed and in retreat. The result of this was that the Scots held a large tract of Northern England and the King, who by this time was having even more trouble with his Parliament in England had to negotiate a reconciliation first in Ripon and then in London.

For the first time the Covenanters in Scotland and the Parliamentary party in England joined forces in 1643. They formed the Solemn League and Covenant binding themselves to seek reformation of the Church which many great and devout men had sought to do in the past, both North and South of the border.

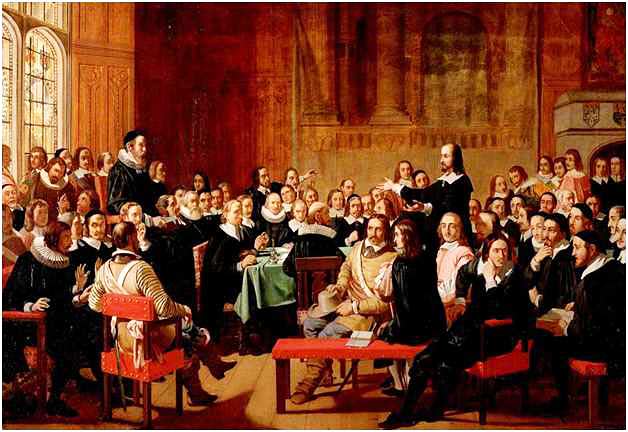

The Westminster Assembly

The outcome of all this was the Westminster Assembly of Divines. Rutherford was one of the Church commissioners sent to London by the Scottish church, along with Alexander Henderson, George Gilespie, Robert Baille and Archibald Johnstone.

Rutherford moved to London, and stayed from November 1643 to November 1647. Besides the work spent on preparing the Westminster Confession of Faith he was one of the main contributors of the Larger and Shorter Catechism in October 1647.

It would be true to say that bearing in mind the various views held by the 151 members present, controversy was inevitable. Rutherford was among the foremost in voicing his opinions and was often puzzled by the theological stance of good men who opposed him.

This Westminster Confession was of course the basis of many others, and the 1689 Baptist confession is, in many aspects based on this.

Rutherford Takes Up His Pen

As well as working on the Westminster Confession of Faith and the Catechisms, he was writing other books, and during the 1640’s he wrote a trilogy on Presbyterianism.

Rutherford was not just striving to present a credible case for one theory of Church government. To him, the glory of Christ himself was intrinsically bound up with the nature and worship of His Church in its purity and power. The first of these books on Presbyterianism was titled “A Peaceable and Temperate plea for Pauls Presbytery in Scotland”. In its pages Rutherford argues passionately for the rule of the Church according to Presbyterian discipline and principles, basing his argument on injunctions from both Christ and his apostles.

The second book was calIed “The Due right of Presbyteries” and this dealt with answering questions regarding the authority and discipline of the Presbyterian Church, the last in the series came in 1646 and was called the “Divine right of Church government and excommunication”.

In 1648 he wrote”A survey of the Spiritual Antichrist”, in which he dealt with the dangers of Antinomianism which was rife in his day.

He also wrote 2 doctrinal and devotional books. These were “Christ dying and drawing sinners”, and “The trial and triumph of Faith”, the last book being a beautiful narrative of the Lords interview with the Syro-Phonesian woman.

Another book he wrote during this period which was not as well received as the others was called “Free Disputation against pretended liberty of Conscience”. Rutherford argues for the responsibility of man for his belief in religion, and also for the obligation of the church to exclude from fellowship those who have abandoned the faith or who disown their profession.

Rutherford wanted to urge parliament to impose the true Christian faith in a unified national Church, using coercion if necessary.

The error that runs throughout the book, and I quote Andrew Thomson – “Heresy is a crime against the state and especially at the instance of the Church and ought to be visited with civil pains and penalties”, it all seems so out of character of Rutherford and the dangerous route he was taking, it may be that he was being misunderstood or misinterpreted but there was this current idea of applying the analogy of the Jewish Old Testament theocracy to human government in Scotland.

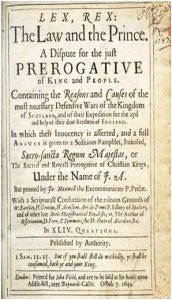

Lex Rex – The Law and The Prince

In 1644 he wrote his most famous and controversial book entitled “Lex Rex”, or the “The Law and the Prince” and next to his “letters” this is one of his achievements for which he is best remembered.

This book was not just a spiritual treatise on the subject of the Church and the State, but it has been noted as one of the most valuable contributions to political science ever written. Many of the principles here soon found their way into the constitution of countries around the world.

In the 1640’s it caused great excitement, the book was extremely popular and sold in vast numbers for its time. The country was at the time embroiled in the Civil War and Rutherford was fighting with his pen rather than a sword, and his book argued powerfully against the arbitrary and tyrannical rule of the monarch.

Although he strongly advocated the obedience and loyalty of a subject to his ruler, he also insisted that a king who perverted justice and oppressed the rights of the people could forfeit that right of kingship. Lex Rex has been described as one of the most ablest pleas in defence of a Constitutional and democratic government.

To the King however such writings were inflammatory. Fifteen years later the book was to be condemned as treasonable and copies of it were to be publically burned and eventually a proclamation was made that every person found with a copy of Lex Rex would be regarded and treated as an enemy of the King.

Back to Scotland

Rutherford returned home to his beloved Scotland on November 9th 1647, and the remaining 14 years of his life were to be spent at St Andrews. On his return he was made the Principle of St Mary’s College and later he was to be the Rector of St Andrews University. Rutherford was by this time very well known and other institutions began to seek him for themselves. Firstly he was invited to become the Professor of Divinity and Hebrew at Harderwyck in Holland but he declined. Three years later in 1651, the University of Utrecht twice invited him to fill the position of Professor of Theology; Rutherford hesitated for 6 months as to what to do but at length the disturbed condition of the Church of Scotland turned the balance in favour of staying at home.

The Solemn League & Covenant – Consequences

The civil war was now over. The King had surrendered to the Scottish army when it was in the Midlands in the hope of saving his throne, for he knew that if he gave up to the English he would be compelled to abdicate. The Scots insisted however on his agreement to establish Presbyterianism in England in return for saving him and moved northwards taking him with them back to Scotland . But he refused so the Scots handed him over to the English who promptly imprisoned him in Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight.

It then seems that certain Scottish nobles attempted to come to an understanding with Charles 1st whereby he assured them that he would uphold the Solemn League and Covenant and establish Presbyterianism in both England and Scotland for a trial period of 3 years.

Why the Scots believed him this time no one knows, but the Scots now under the Duke of Hamilton in 1648 raised an army and fought against Cromwell in support of the imprisoned King and were soundly beaten at Preston.

Samuel Rutherford and many other Covenanters were vigorously opposed to this action and they got the Scottish Parliament early in 1649 to pass what was called “The Act of Classes”, this divided people involved in the support of Charles 1st into “classes “according to their degree of disaffection to the Covenant. It prohibited many from holding any military or civil office from 2 years to life depending on the circumstances.

Unfortunately no sooner had the Act been passed that Charles I was brought to his untimely end at the gallows in London.

The Scottish nation was deeply upset by this action, many folk were dismayed and there was a great anti-Cromwell movement which lead to the Scots seeking Prince Charles to be the new King. This of course, as history tells us, was a great mistake. The Prince was brought from the continent to Scotland whereupon after a lot of argument and arm twisting he swore allegiance to the National Covenant. Charles’s mother, Henrietta Maria, was to say to him “Promise the Scottish people anything to win their support, then free yourself at the first opportunity”. So He was crowned King Charles 2nd of Scotland, England and Ireland at Scone in January 1st 1651.

Cromwell would not allow Scotland to establish Charles II as king. The Scottish army rose up against Cromwell and was beaten. Charles fled back to the Continent and the Scottish people must have wondered what had happened. Rutherford and many others were dismayed to find that the Scottish Parliament then wanted to rescind the Act Of Classes on the pretext that the army was short of good soldiers, and in JuIy 1651 the Scottish Parliament passed the “Public resolutions” allowing all enemies of the covenant back to office.

Rutherford vigorously opposed this move and tabled a “Protest” fearing that the Covenant itself and Reformation principles were at stake, and he was right of course. Godless and unprincipled men, readmitted at this time were later to become the relentless persecutors of the Covenanters”.

Division in the Church – Protesters & Resolutioners

What concerned Rutherford most was not so much the political situation which was chaotic but the deep division that was splitting up the Church into two hostile camps. They called these two positions the Protesters and the Resolutioners, the origins of this split are difficult to grasp, but the controversy was to tear the Scottish Church apart for years.

This split between the Resolutioners and the Protesters was to develop Into a most damaging schism. Out of the 5 commissioners sent to the Westminster Assembly only three were still alive, two of them, Rutherford and Archibald Johnstone, led the Protesters while Robert Baillie led the Resolutioners, with many other good men being on either sides of the divide.

This period in Rutherford’s life has been described as a sad interlude by Faith Cook, in her book; he was obviously deeply concerned at the developments within the Church and said some bitter and hurtful things to those who didn’t agree with him.

Some of his letters of the time to correspondents share some of the inner turmoil he was feeling. In one of these letters he says – “We are now shouldering and casting down one another in the dark and the godly are hidden from the godly”.

In a record of one of his preaching sermons in Edinburgh he said – “Woe is unto us for these sad divisions that make us lose the fair scent of the Rose of Sharon”.

The Resoloutioners were acting in the light of the military situation in Scotland and they were in a great majority over the Protesters who were few but vocal. Subsequent history was to show that the Protesters had their eyes open while the Resoloutioners were blind to see the problems, but the Protesters were treading dangerous ground because they were basically saying and I quote “that the army and civil officers should be composed of saints only”.

Rutherford’s home life had been particularly distressing, as has already been mentioned his first wife Eupham died back in 1631, his two children by her died in infancy. Now out of the seven children born by his second wife Jean, six had died in infancy and early childhood, and only one girl called Agnes was to survive him.

Towards the end of the 1650’s the political situation in Scotland and England was deteriorating. Oliver Cromwell died in 1658 and the job of Lord Protector went to his son Richard, who was nothing like his father and he abdicated within 12 months. This lead the way open for Prince Charles who had fled to the continent to come back. In the spring of 1660 he returned, and with great pomp and ceremony was crowned King Charles 2nd.in Westminster Abbey.

A Time of Trial & The King’s Vengeance

So began a great time of trial for the Christians North and South of the border.

The first incident to strike the Scots was when the Marquis of Argyle, Lady Kenmores brother who had actually placed the crown on young Charles head back in 1651, went to London to congratulate the returning monarch and was immediately imprisoned in the Tower of London and was later executed.

It became blatantly obvious to the Scots that they had been deceived and betrayed. The young Charles who had sworn allegiance to the National Covenant and promised to uphold Presbyterianism had now done an about turn and his true disposition was revealed. The thousands of Scots who had fought in the army on his behalf against Cromwell and had died had done so in vain.

Vengeance was in the heart of the new king towards the Presbyterians of Scotland. Rutherford together with Archibald Johnstone and James Guthrie a minister from Stirling were now marked men.

On January 1st 1661 in one sweeping measure the Scottish Parliament under orders from the new King passed the Act of Rescissory which meant that all the previous Acts of Parliament passed since 1638 were to be nuII and void, the National Covenant was revoked and the Presbytery abolished.

The Presbyterian ministers would unless they compromised their beliefs soon be thrown out of their churches and have to hold meetings in barns and private houses, eventually these were impossible too and irregular meetings would be held in the remote countryside which they called Conventiclers. The moors and glens of Scotland would soon become a hunting ground on which those who refused to worship God according to forms which they believed were unscriptural and sinful, were to be persecuted and slaughtered. Many hundreds of the covenanters would die for their faith over the next 30 years.

Guthrie was the first to suffer. He was imprisoned then later executed. Rutherford was another of the 4 marked for execution. He had already been thrown out of the University, and deprived of his pastoral charge, but by now he was a sick man. When the Kings emissaries arrived with a summons to arrest him he was already dying, so Rutherford eluded the doom intended for him because the finger of God beckoned him to far better things. Rutherford said “I have a summons already from a superior Judge and I behove to answer my first summons and when your day arrives I shall be where few Kings and great folks come”.

Glory, Glory Dwelleth in Immanuel’s Land

Rutherford lived to see all that he had striven for over thirty years crumbling before his eyes. An ideal church both in order and worship had been his vision, but the enemies of the gospel had ruthlessly trampled on all his achievements. Even with all these disappointments he never lost his zeal and love for his God and his Saviour.

As he endured his final painful weeks Rutherford meditated on his two favourite themes, the beauty of Christ and the joys of heaven. He said – “My honourable Master and lovely Lord, my great royal King has not a match in heaven nor in the earth. I have my own guilt, but he has pardoned, loved, washed and given me joy unspeakable and full of glory”.

His friends, his wife and surviving daughter gathered around his death-bed and heard his last recorded sayings on earth when he said – “Glory Glory dwelleth in Immanuel’s Land”, and so Rutherford obeyed that summons from the superior Judge and stood before His King of Kings and Lord of lords.

Those last words have been written into one of our best known hymns, which is still in our hymn books today, written in 1857 by Anne Ross Cousins, a poet and hymn writer, the wife of a Presbyterian minister in Irvine, and it is called Rutherford’s hymn – “The sands of time are sinking” originally had 19 verses, and was a biographical hymn of his life. For our hymn book this has been shortened to 6 verses. Apparently this was the last hymn given out by C H Spurgeon at a brief service in his rooms in Mentone, Southern France, just before he died in 1892.

Rutherford lived through very difficult times, he was a very complex figure and describes himself as a man of extremes who was at times very controversial . Edward Donnelly writes that he was a gifted writer and theologian, a University lecturer, involved crucially in church affairs in Scotland and in the Westminster Assembly, yet what he preferred was preaching in the countryside to a small congregation of ordinary people and giving warm pastoral advice to those in need. Nowhere does this come out more than in his letters.

The Pastoral Letters of Samuel Rutherford

Rutherford’s letters, and there were over 360 of them, have been described in glowing terms by readers who have benefitted from them over this span of time. When they were first written they were for the personal reading by the recipients, but in many ways they are timeless and open for all. The popular book containing his letters has been reprinted many times up to the present day.

Many people have spoken highly of Rutherford’s letters and the spiritual benefit and knowledge that they have received from them. Robert Murray M’Cheyne said that the letters were almost daily his delight.

Charles Haddon Spurgeon said – “There is to us something mysterious, awe-creating and super- human about Rutherford’s letters” and in 1891 he wrote – “what a wealth of spiritual ravishment we have here, Rutherford is beyond alI the praise of men like a strong winged eagle he soars into the highest heaven and with unblemished eye he looks into the mystery of love divine.” Spurgeon also went on to say – “when we are dead and gone let the world know that Rutherford’s writings are the nearest thing to inspiration which can be found in the writings of mere men”.

John Wesley wrote in 1767 – “These letters have been generally admired by all the children of God for the vein of piety, trust in God and holy zeal which runs through them”.

In conclusion here are parts of 4 letters written in different circumstances.

~~~~~~~~~~

First we have part of a letter to a Christian lady, written from Anwoth in 1628 shortly after he started his ministry there. This shows how Samuel Rutherford lovingly empathised with the lady upon the death of her daughter and urged her to consider the blessings of suffering as it draws the believer into closer fellowship with Christ.

“Mistress,

My love in Christ remembered to you. I was indeed sorrowful at my departure from you, especially since you were in such heaviness after your daughter’s death: Yet I do persuade myself, you know that the weightiest end of the cross of Christ that is laid upon you lieth upon your strong saviour. For Isaiah saith that in all your afflictions He is afflicted. Oh blessed One, who suffereth with you! And glad may your soul be even to walk in the fiery furnace with one like unto the Son of Man, who is also the Son of God. Courage up your heart: when you tire he will bear both you and your burden.

Yet a little while and you shall see the salvation of God.

Remember of what age your daughter was, and that just so long was your lease of her. Indeed that long loan of such a good daughter an heir of grace, a member of Christ as I believe deserveth more thanks at your creditor’s hand that you should murmur when He craveth His own.

But what! Do you think her lost, when she is but sleeping in the bosom of the Almighty. Think of her not absent who is in such a friend’s house. Is she lost to you who is found in Christ!”

He closes the letter with – “Run your race with patience, let God have His own and ask of Him instead of your daughter whom he has taken from you, a daughter of faith which is patience. Lift up your head, you do not know how near your redemption doth draw. Thus recommending you to the Lord who is able to establish you I rest.

Your loving and affectionate friend in the Lord Jesus.”

~~~~~~~~~~

The second was written from Aberdeen to an unconverted farmer living back near Anwoth who he obviously had previously spoken with. It shows how earnestly he pleaded with him to seek for his salvation, and Rutherford did not mince his words – a challenge to us in our day and age.

“Loving Friend.

I earnestly desire your salvation. Know the Lord and seek Christ. You have a soul that cannot die. Seek for a lodging to your poor soul, for that house of clay will fall. Heaven or nothing! Use prayer in your house and set your thoughts on death and judgement. It is dangerous to be loose in the matter of your salvation. Few are saved, men go to heaven in ones and twos and the whole world lieth in sin.

Love your enemies and stand by the truth which I have taught you in all things. Fear not men, but let God be your fear. Your time will not be long, make the seeking of Christ your daily task.

Ye may, when ye are in the fields speak to God. Seek a broken heart for sin, for without that there is no meeting with Christ.

Grace be with you.

Your loving pastor.”

~~~~~~~~~~

Thirdly , a very different letter from Samuel Rutherford after he was banished to Aberdeen, written in 1637 to Marion M’Naught who attended the church in Anwoth – it is called – A Spring Tide of Christ’s Love. It shows that even in the midst of solitary confinement Rutherford experienced in a special way the eternal love of the Lord.

“My dear and well-beloved sister,

Grace, mercy and peace be to you..

I am well, honour to God. I have been before the court set up within me of terrors and challenges, but my sweet Lord Jesus hath taken the mask off his face and said “Kiss thy fill” and I will not smother nor conceal the kindness of my King Jesus. He hath broken in upon the poor prisoner’s soul like the swelling of Jordan. I am bank and brim full, a great high spring tide of the consolations of Christ hath overflowed me.

I would not give my weeping for the fourteen prelate’s laughter. They have sent me here to feast with my King Jesus. His spikenard casteth a sweet smell.

The Bridegroom’s love hath run away with my heart. O love, love, love. O sweet are my royal kings chains! I care not for fire nor torture.

Pray for my poor flock. I would take penance on my soul for their salvation. I fear that the entering of a hireling upon my labours there will cut off my life with sorrow. There I wrestled with the Angel and prevailed. Wood, trees meadows and hills are my witnesses that I drew on a fair meeting betwixt Christ and Anwoth.

Forget not Christ’s prisoner.

I long for a letter under your own hand.”

~~~~~~~~~~

Then finally we have a letter to Lady Boyd from Kilmarnock who was a long-standing friend, written in 1644 when he was in London. The letter is about the proceedings of the Westminster Assembly. It is interesting because of his obvious disagreement with other Godly puritans like Thomas Goodwin, and Jeremiah Burroughs the author of the well known book “The Rare Jewel of Christian Contentment), both men who we would hold in high esteem.

“Madam.

Grace mercy and peace to you. I received your letter on May 19th. We are here debating with much contention of disputes for the just measure of the Lord’s temple. It pleaseth God that sometimes enemies hinder the building of the Lord’s house, but now friends, even gracious men, so I conceive them, do not a little to hinder the work. Thomas Goodwin, Jeremiah Burroughs and some others four or five who are of the Independent way stand in our way and are mighty opposites to presbyterial government.

The truth is, we have at times grieved spirits with the work and for my part, I often despair of the reformation of this land, which saw never anything but the high places of their fathers and the remnants of Babylon’s pollutions.

And except that “not by might, nor by power, but by the spirit of the Lord”, I think God hath not yet thought it time for England’s deliverance.

Grace, Grace be with you,

Amen”

~~~~~~~~~~

In a conclusion from Kingsley Rendell he says – “There is little doubt that Rutherford will remain something of an enigma to all who study his life and ministry. The letters portray him as a saint, but he owned himself a sinner. He was so sure of heaven, yet in moments of depression he was beset with doubts and misgivings. He was heavenly minded and yet he was so involved in the politics of earth.

He was a democrat yet an autocrat a man who demanded liberty of conscience for himself yet was reluctant to grant it to others.”

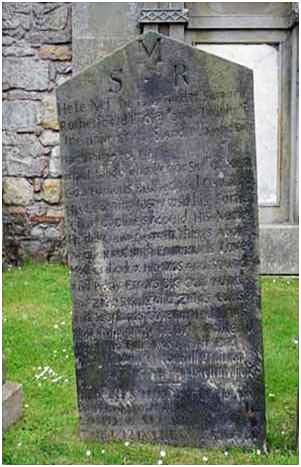

The life and ministry of Samuel Rutherford is summed up in words upon his gravestone in St Andrews.

For Zion’s King and Zion’s cause

And Scotland’s covenant laws

Most constantly he did commend

Until his time was at an end

Then he won the full fruition

Of that which he had seen in vision…

~~~~~~~~~~

Acknowledgements

Samuel Rutherford and his friends by Faith Cook.

Samuel Rutherford by Richard M Hannula.

Letters of Samuel Rutherford published by Banner of Truth.

Samuel Rutherford by Kingsley G Rendell

Men of the Covenant by Andrew Smellie

Photos from Google photos and Wikipdia.