William Williams – The Hymn Writer

A talk given at Crich by Chris Clarke

William Williams has been described as the sweet singer of Wales – and is arguably Wales most famous hymn writer.

William Williams actually wrote over 900 hymns in either Welsh or English, the most famous being “Guide me O thou great Jehovah”, which has been in the Top 10 of the Songs of Praise for years; was sung by the Welsh Regiments in the trenches in the First World War to keep their spirits up; is sung with great gusto before the Wales home rugby matches at the Millennium Stadium; and was even read out as a poem at the ordination of George Carey as Archbishop of Canterbury.

I’m not sure if Williams would appreciate any of these claims to fame!

In Wales today although many of his contemparies are largely forgotten, Williams is remembered not only because of his hymns. But also recent fresh interest centres on his poetry as a whole as well as his prose. He has been described as the first romantic poet in Wales and as such has exercised considerable influence not only on his contemporaries but also on his successors.

Dr Martyn Lloyd Jones says “Certain literary authorities in Wales who are not Christians themselves are ready to grant that he is in their judgement the greatest of all the Welsh poets”, he goes on to say “that this is something of very real significance, because here you have such an outstanding natural poet now under the influence of the Holy Spirit writing these incomparable hymns”.

In Wales today he has almost iconic status as a poet and bard of Welsh culture, poetry and prose. In the Town hall in Cardiff there is a sculpture of him carrying a book in his hand.

The University of Wales Press are in the process of reprinting his entire works (in Welsh of course).

For one who was such a prolific writer, it is interesting that he wrote nothing about himself. He did not write an autobiography or keep a diary. – Maybe he was too busy in his work or perhaps didn’t consider that what he was doing warranted it. The first biography appeared in Welsh 22 years after his death written by his friend Thomas Charles of Bala. It was called “The Spiritual Treasury” and was not much longer than an essay as it was only 12 pages. It was not until 1867 that a biography and study of his works was written by J R Kilsby Jones, a Congregational minister, in his book roughly translated “All the poetic and prose work of William Williams” it ran to 846 pages.

Thomas Charles was to write of William Williams: – “When God fills people’s souls with the knowledge of Christ, who can keep it in. I have observed and seen in the mountains of Wales the most glorious work that ever I saw. The gospel has run over the mountains between Breconshire and Monmouthshire as the fire in the thatch”.

Doctor Martin Lloyd Jones described William Williams as the best hymn writer there has ever been saying – Quote “The hymns of William Williams are packed with theology and experience, You get greatness, bigness and largeness with Isaac watts, you get the experiential side wonderfully in Charles Wesley but in William Williams you get both at the same time and that is why I put him in a category entirely on his own – he taught the people theology through his hymns”.

An example of this is in the following hymn which was one of the last he wrote in 1772 and was included in his book Gloria in Excelsis

Awake my soul and rise

Amazed and yonder see

How hangs the mighty Saviour god

Upon a cursed tree

How gloriously fulfilled

Is that most ancient plan

Contrived in the eternal mind

Before the world began

Now hell in all her strength

Her rage and boasted sway

Can never snatch a wandering sheep

From Jesus arms away

This is an excellent example of one of William William’s hymns; it shows the sovereignty of God from eternity and the plan of salvation through our Lord Jesus and ends with the warming thought that Christians are safe in Jesus’ arms.

Now to give a little background to William.

He was born in the early part of 1717 at Cefncoed a farm approximately 3 miles from Llandovery in Carmarthenshire. His father John was a farmer and was the ruling elder in the non-conformist Congregational Church in Cefnarthen and he was one of the pillars in the chapel. His mother Dorothy Lewis was 30 years younger than her husband John and they had 6 children 3 sons and 3 daughters. William was the 4th child, who was the only son to survive into adulthood, together with one sister Mary.

The farmhouse at Cefncoed today, where William Williams grew up.

The Church in Cefnarthen.

Dorothy’s family lived in another farm about a mile away called Pantycelyn she had 2 unmarried brothers who died quite young, so upon the death of her parents she inherited the farm and when her husband John died at the age of 86 in 1742 she moved back to Pantycelyn with her son William and she remained there until her death in 1784.

The farm Pantycelyn today where William spent most of his life

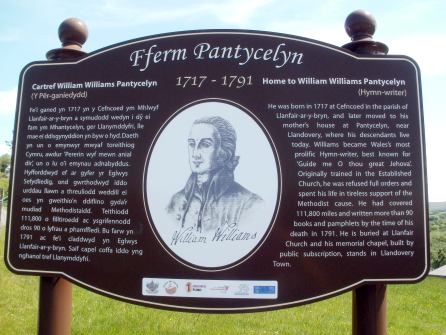

Fferm Pantycelyn – The Heritage Board at Pantycelyn, in English and Welsh

Going back briefly to William’s father John, the church in Cefnarthen suffered a serious split sometime between 1736 and 1740. The church was torn between a group that favoured Arminianism after the arrival of a new minister which was much larger group and another group of Calvinists. It is recorded that John as the ruling elder left the church with a group of fellow Calvinists to form a new Church, meeting in a house in Clunpentan . It is said that the Calvinists multiplied but the Arminians declined. Many years later in 1749 Dorothy and her son William gave a portion of land and a cottage for the church to build a new Church building in the next door village of Pentre Ty gwyn. It is not known what effect all this arguing and controversy had on the young mind of William. Neither do we know if William took part in these controversies. All we know is that he attended the church.

Very little is known about William’s life growing up on the farm in South Wales, he obviously attended the non-conformist Church in Cefnarthen with his parents. William was educated by a neighbour Morgan Williams who was learned in English and Latin and sometime later he went to a school which was opened in Llandovery by the SPCK (The society for the promoting of Christian Knowledge).

When William was 17 or 18 he left home to complete his education at the Llwynllwyd Academy. Which was near to Hay on Wye. He went there with the idea of becoming a doctor (medical training was different then to now) because the academy was also an institution for preparing young men for the ministry and during the 3 or 4 years he was there he would have spent some time with them.

Williams’s arrival at the Academy in 1734 coincided with another great event. It was around this time that a young teacher of 24 year old Howell Harris was converted and he lived just 6 miles way. After Howell’s conversion he was very active in the area in open air preaching, exhorting his friends and neighbours and with his passionate preaching was stirring up the people to seek forgiveness of sins through the sacrifice of Christ.

It is quite likely that William and his fellow students would have heard about this and they may have visited nearby Talgarth where Howell lived with the sole intention of hearing him. It is not known if William made this journey to hear him preach.

But in 1738, on one occasion William started to make the journey back home from the Academy. This would have involved passing through Talgarth, it was Sunday morning and as he walked through the churchyard he could hear a man preaching in the open air standing on a gravestone. He could see a crowd was gathered around listening intently. William went across to see to and it was there that William heard preaching the like of which he had not heard before. As Harris pleaded with his hearers and warned them of coming judgement, the anticipation turned to terror on many of the faces. The effect on William was swift and dramatic as the Spirit of God applied the words to his conscience… The debt he owed to Howell Harris was one he never forgot.

The Church at Talgarth where William Williams heard Howell Harris preach

This is how William expressed his thoughts in a poem about his conversion that Sunday morning in 1738.

This is the morning, still remembered

That I first heard heaven’s sound

By a summons straight from Glory

With his voice my heart was bound.

That’s the spot forever treasured

Where I first his visage spied

At the Church’s portly entrance

With no path on any side

In a solemn serious spirit

With eternity in sight

Urging, pleading with the people

From God’s wrath to take their flight.

After his conversion William seems to have completed his studies, and as well as medicine he would have been tutored in the Greek and Latin classics, Hebrew Logic and Mathematics. However, William was now a changed man and felt that he had to preach the Gospel rather than become a doctor. He was to become a physician of souls rather than a physician of bodies – a reminder to us of Doctor Martyn Lloyd Jones many years later.

Harris was an Anglican and with his preaching having great effect throughout South Wales, he was forming small groups called seiadaw societies or later grouped into associations for his converts. William was to join up with Harris and his friend Daniel Rowlands from Llangeitho to form a friendship that would last all their lives. Dr Martyn Lloyd Jones in his paper on Welsh Calvinistic Methodists describes these men as the great leaders of the Calvistic Methodists in Wales in the 18th Century, he describes Daniel Rowland as the outstanding preacher, Harris as the great exhorter and organiser and William Williams as not only as a poet and writer of hymns which we will come to later but also the great theologian of the group.

It is also clear that the influence of Harris and Rowlands upon William was behind his decision to join the Anglican Church and apply to become a curate. This does seem rather strange bearing in mind his being brought up in a non-conformist family but it may be due to living through the various squabbles at his father’s Church and during the time he was away at college the church had split completely that may have been instrumental in making this decision. William has come in for some criticism for joining the established church. It is also true that Harris and Rowland’s both being in the established church felt that the great need of the age was get more men of ability and learning as clergy and they saw in William a man whose heart burned in love for his Saviour, and compassion for the state of the people and the land. In William they saw a chosen vessel of God and the best place for him in their opinion was in the ministry in the established church.

So on Sunday 3rd August 1740 William was ordained as a deacon by Nicholas Claggert, the Bishop of St David’s, to the curacies of 3 local churches in the villages of Llanwrtyd and Abergwesyn, and he was to serve there as curate for the next 3 years, where he was paid an annual stipend of £10 per year. These villages were in a very sparsely populated area 12 miles from his home in Cefyn Coed, just over the border in Breconshire. There was no accommodation provided and he had to make Cefen Coed his base. With the friendship and influence of Harris and Rowland as well as preaching at these remote churches, William was also preaching in the open air and at other places outside the parish. Harris heard him preach on one occasion on Ezekiel 33 v 11.

“Say to them, As I live “says the Lord God “I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but that the wicked turn from his way and live. Turn, turn from your evil ways. For why should you die O house of Israel”

Harris wrote in his diary “convey the impression of youthful zeal, uncompromising candour, and a fiery passion in delivery”. He goes on to say that “the sermon was rich in biblical allusion and fervent in personal application and Harris was profoundly moved.”

However difficulties also arose, first he was very ill with smallpox, then his father who had been blind for a number of years died. Then complaints were made to the Bishop detailing 19 irregularities mainly to do with William not making the sign of the cross when baptising infants and of course crossing parish boundaries, which according to the Church authorities was not allowed… This rumbled on for 2 years, he appealed twice and there were 6 hearings but in the end he was not allowed to go forward for full ordination and was dismissed from the curacy.

Despite these difficulties and while the appeals were on-going, William was greatly encouraged when on January 5th and 6th 1743 he attended the first Association of the Calvinistic Methodists meeting held in Watford near Caerphilly. Among those present were John Cennick, Joseph Humpries, John Powell, William Williams, George Whitfield, Daniel Rowlands, and Howell Harris.

At this meeting George Whitfield on hearing all about William and his current difficulties, encouraged him to go into the fields and bye ways and preach. Another significant item agreed at that meeting, was that William should become Daniel Rowland’s assistant and this he would continue for the rest of his life.

We need to just take a step back at this stage and consider what was happening in the Church in Wales at this time.

Firstly the Calvinistic Methodists – this could be a meeting in itself. Many in the past have thought this a contradiction in terms and in his paper Dr Martyn Lloyd Jones explains; quote – “that although we may think the terms “Methodist” and “Calvinistic” cannot be linked together and are incompatible.” He explains that “Methodism was not primarily a theological position and it was not a movement designed to reform theology. It was essentially experimental or experiential religion and a way of life”.

So in the case of these Calvinistic Methodists in Wales in the mid 18th century, they were entirely Calvinistic as in contrast to the situation in England, with influences from the Wesley’s etc. The Methodism in Wales was entirely Calvinistic and to a large extent this was due to the influence of George Whitfield who was the moderator at that first Association meeting in 1743, and he spent some considerable time in Wales working with Harris, Rowland and Williams.

The other point to remember is that it was during this period that God greatly blessed the land of Wales with many revivals and vast numbers were converted under their preaching and ministries. This in itself posed a problem. Basically what to do with all these new converts. This proved to be something of a dilemma Even though they had difficulties with the Anglican authorities they were all firm Anglicans

Dr Martyn Lloyd Jones in his paper has a quotation, which summed up said that … ‘the Anglican Church at this time had – Calvinistic articles, Romish liturgy and Arminian ministers who were also spiritually asleep’. On the other hand they didn’t have a high opinion of the non-conformists the Presbyterians, Congregationalists, or Baptists either who he goes on to say “although there were good men they were given to argumentation and disputation between themselves.” And although this may be a bit of generalisation there must be a degree of truth in this.

As a result of this they encouraged the new converts to join with the established church but also set up the societies in every locality. By 1750 there were 450 of these societies and so the Calvinistic Methodists continued as a church within a church until 1811 when the first Methodist minister was ordained and they officially started their own denomination.

But for now as Rowland’s assistant, William had the responsibility of overseeing a large number of these Welsh Methodist Calvinistic societies across South Wales and over the next 48 years he wrote that he had travelled some 150,000 miles, preaching, teaching and leading these meetings. This would have been on foot or horseback.

On 3rd February 1744 at one of the monthly Association Meeting in Carmarthenshire Harris raised the question of the need of a poet to set the truths of the gospel into song in the same way as Charles Wesley was doing in the English Methodist movement. Each man was invited to write a hymn and submit it to the others for assessment to see whether God had given to any the gift of writing hymns. The work submitted by William so far outshone that of the others that he was quickly commissioned to compose hymns which would set the welsh people singing the truths to complement the preaching.

It is most likely that he started writing poems and hymns soon after his conversion, his school book belonging to him was found with one of his relatives containing some 800 verses, and it is clear that this material was used as a basis for the hymn books which were to follow

William must have been very busy as in September of 1744, an advertisement was displayed-

‘My fellow countrymen. This is to announce that 9 godly hymns on various subjects from the work of William Williams are to be printed with all haste- price one penny and for sale in Carmarthen by John Morgan in Water Street.’

This was William first venture into print and proved sufficiently popular to require a second printing before the end of 1744.

In 1745 the second collection appeared while the 6th collection and last part appeared in 1747, a total of 155 hymns including “Guide me O thou Great Jehovah”.

In the preface William describes the subjects which his verses address as assurance of faith, spiritual joys, longings for heaven and triumph over the enemies of the gospel. The people received his work with delight. Many of his fellow countrymen were illiterate, few had access to the scriptures and through the hymns that William wrote, the people learned their theology as they sang the great truths of the faith.

In 1748 William married Mary Francis who lived in nearby Llansawel. She had previously helped the Rev Griffith Jones to set up the Welsh Circulating Schools and was a very capable person who also had musical gifts and she used to sing William’s new hymns to tunes she had heard or composed. So it proved a very useful partnership.

An incident is recorded soon after their marriage, Mary accompanied William when he preached in North Wales “After the sermon they lodged at the Pennybont inn. Some persecutors and ruffians found out where they were staying and barged into the parlour with a fiddler. Come in come in cried William. The fiddler in mock courtesy asked if they wanted a tune. What tune, asked the fiddler? Any tune you like replied William. The fiddler began and William called out to Mary to sing – imagine this witness in the Inn that evening, such was their zeal for the Gospel.!

Fly abroad thou mighty gospel

Win and conquer never cease

May thy lasting wide dominion

Multiply and still increase

Sway thy sceptre

Saviour all the world around.

Mary was an only child and upon the death of her parents she inherited a number of properties and land, this together with land and properties William had from his mother enabled them to be very comfortably off and when some of these properties were sold off, the proceeds were to help with the publishing of his books and hymn book.

With the exception of the short time he was employed as a curate, William didn’t receive any salary or wage. William and Mary were to have 8 children 2 boys both of whom were to go on to be preachers and 6 girls, with one dying in infancy. They lived with William’s mother in Pantycelyn which became the family home and is still today in the hands of one of his relatives.

After the success of his first hymn book, new hymns continued to flow from his pen until 1787.

His next hymn books again in Welsh were roughly translated:-

The Songs of those who stand upon the sea of glass in 1762

Farewell to visible things welcome invisible things in 1763

Gloria in Excelcis in 1771

Thankfully he also produced 2 hymn books in English

Gloria in Excelcis in 1772

Hosannah to the Son of David in 1751

Some of William Williams hymns were composed on special occasions such as ‘in times of affliction’ ‘during advent’ and ‘on Christmas day’. Some hymns were written after a request from the countess of Huntingdon for hymns to be used at Whitefields Orphanage in America.

If this was not enough he was also the writer of 8 books of poetical works and 13 books of prose

He even wrote books on subjects as diverse as Marriage, The Aurora Borealis and various scientific developments.

Williams soon became acknowledged by the Welsh nation as a poet of the highest order and he quickly became more acceptable and popular than any previous poet or any to follow after him. His words were eagerly read and sung and his books received circulation greater than any before him. He also printed many of his hymns on sheets of paper and sold them to the poorer believers in the societies as he visited around. It is also suggested that he used to sell tea on his travels and the money for this was also used to publish more books.

As Rowland’s assistant he travelled around the meetings of South Wales, he would often have to sort out difficulties and disputes between members etc, he was apparently a man of kindly and serene disposition and when he was called upon to sort out difficulties, he seemed able to put unresolved issues in the light of eternal truths in a way that made them trivial and even paltry in the eyes of the contending parties.

However in 1750 a dispute arose that even Williams with his disposition was unable to resolve a dispute between the 2 men who he held in the highest esteem Harris and Rowland’s – we don’t have time to consider all this except to say that it is largely agreed that the responsibility for the split was with Harris who had begun to embrace a doctrinal aberration known as – Patripassianism – The teaching that God the Father was also suffering and dying in the person of his Son. This together with behaving unwisely with a lady resulted in him being expelled from the Association which would be split for the next 12 years. Harris returned to his home in Trefeca where he set up a self-supporting Moravian style Christian community.

Although grieving deeply over the sorry position of his friend and spiritual father William remained with Daniel Rowland. throughout the sorrows and pain he tried in vain to reason with Harris to come back into the fold, and during this time William would draw constantly on the grace of God taking him back again to Christ who alone could give him strength.

With the absence of Harris, Rowland’s and William had far more work on their hands and it was during this period that William demonstrated exceptional pastoral gifts, encouraging, consoling, restraining and guiding the societies and It was during this period of distress that many of his hymns and books were penned. Dr Martyn Lloyd Jones wrote about this time – “His genius, his spiritual understanding and what we would now be termed psychological insight stand out everywhere and are truly astonishing.”

By 1762 the clouds that hung over Welsh Methodism began to disperse. Reconciliation at last between Harris and Rowland bought healing to a wound that had festered for too long.

1762 also brought in the floodtide of blessing – God was again pleased to pour out his spirit upon the land and this floodtide of blessing swept across South Wales visiting Churches and Society Meetings. It was in 1762 that Rowland’s was thrown out of the Established Church and his followers built him a new building in Llangeitho. Powerful and penetrating preaching was to have great effect particularly through Daniel Rowland and this was the start of “The Great Revival in the Llangeitho district”, and again William was very involved assisting Rowland’s.

In a letter which William wrote to Thomas Charles, in Bala, he wrote,

“One time there were just a few of us, professing believers, gathered together, cold and unbelievably dead, we were about to offer a final prayer, fully intending never again to meet thus in fellowship in such dire straits, on the brink of despair with the door shut on every hope of success, God himself entered our midst and the light of day from on high dawned upon us, for one of the brethren, yes the most timid of us all the one who was strongest in his belief among us that God would never visit us – while in prayer was stirred in his spirit and laid hold powerfully on heaven as one who would never let go. The fire took hold of others all were awakened the coldest and the most heedless took hold and were warmed. This sound went forth and was spread from parish to parish and from village to village. The tone of the whole district was changed. Today nothing counts but Christ and he is all in all.”

All of this coincided with the publication of one of William’s new hymn book – The songs of those who stand on the sea of glass in 1762.

As they were to sing these moving truths of God’s grace to sinners, hearts were set aflame and many traced their conversion to this time of refreshing. The people clamoured to obtain copies of his hymn book and the book rapidly went through 5 editions. One of the most famous –

Onward march all conquering Jesus

Gird thee on thy mighty sword

Sinful earth can ne’er oppose thee

Hell itself quails at the word

~~~

Even today I hear sweet music

Praises of a blood freed throng

Full deliverance, glorious freedom

Are the themes for endless song?

~~~

Whiter than the snow their raiment

Victor palms they wave on high

As they pass with fullest glory

Into life’s felicity

As they sang such words, the people were often unable to contain their exuberance and the gladness of heart that welled up within them. They would be literally leaping and jumping for joy. Such physical manifestations brought a considerable amount of criticism on this new work of God from all quarters and William had to defend these genuine expressions of spiritual delight from hostile censure

Thomas Charles wrote in his biography of William: – “He would frequently mount on very strong wings which would lift him to the heights of splendour – some verses of his hymns are like coals of fire warming every passion when sung”.

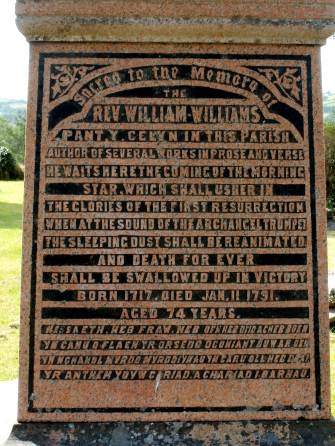

From 1776 onwards there is a marked scarcity of any records of his movements, he continued to preach and lead the society meetings, and he also continued to compose hymns, wrote prose and translates tracts and articles. His health during this time caused him many difficulties. He suffered from Kidney stones for those last 15 or so years, and he died on January 11th 1791 at the age of 74. He was buried in the parish church at LLanfair – ar-y-bryn.

The memorial stone in the churchyard at LLanfair – ar- y-bryn

A memorial chapel was built in the main street in Llandovery between 1886 and 1888 and today his name is synonymous with the town of Llandovery, with the local school even being called after his name.

The Memorial Chapel in Llandovery

William’s 2 sons John and William both went into the ministry, William became a Church of England minister and ministered in Truro in Cornwall all his life, while John became the first principle of the Trevaca Academy for ministers which had been set up by the Countess of Huntingdon and Howell Harris and opened in august 1768 it was called “A school of the prophets!

That was the life of William Williams, but what of the legacy he has left for us today. As I said he wrote nearly 900 hymns mostly in Welsh and not surprisingly the ongoing influence and number of hymns still used does depends which side of the Severn Bridge you live.

The Welsh Methodist Hymnbook contains 238

The Welsh Baptist Hymnbook contains 152

The Welsh Congregational Hymnbook contains 138

The hymn book used by the Reformed Welsh Speaking Churches in Wales today titled “Caneuon Ffydd” – translated as “Hymns of the fellowship” it contains 98 out of a total of 900.

Coming into England

Older hymnbooks such as Golden Bells and Hymns of Faith have just 3

The book we use, namely Christian Hymns, contains 13

One wonders whether the number of William’s hymns in Christian Hymns is due to the late Graham Harrison who was one of the editors, who was himself a Welshman.

Generally his hymns are an expression of experiential faith, of a pilgrims journeying through life and looking forward to eternity in heaven. The hymns we have although small in number are hymns rich in theology and experience.

As Glyn Hughes says…. “the constant and powerful undercurrent of Pantycelyn’s hymns is the emphasis on the divinity of Christ’s love and man’s total dependence on God’s saving grace. William’s hymns were the real Confession of faith of the Methodists, and they became in the course of the 19th century some kind of Confession of experience for the majority of Welsh believers.”

Who better than William Williams himself can explain his purpose in writing hymns. I quote from the preface to his hymnbook called Alleluia……

‘The devil shows great diligence and subtlety secretly to entice and direct your thoughts away from God, and from eternal things, to worldly and temporal affairs. Not only is fervent prayer an excellent remedy against this, but also among many other things it is necessary to establish your mind and memory on the Scriptures (which are in God’s hand the sword of the Spirit against the devil’s schemes). Being aware of these things and in order to help you in this, I have written for you some hymns, composed as near as possible to the sound and language of the Scriptures, so that in song they might come more easily to mind and be more effective in working on your affections.’

Faith Cook in her book – Our Hymn Writers and their hymns “notes the guidelines which William Williams laid down for would be hymn writers…

1) To seek for real grace themselves and a saving knowledge of God in his Son, for without such qualification it is a most daring presumption to touch the ark

2) To read every work of poetry they may obtain to enlarge their understanding, to know poetry well, to perceive where its excellence exists.

3) To read over and over again the works of the Prophets, the Psalms, Solomon’s Song, the Lamentations, the Book of Job and the Revelation which are not only full of poetical flights, figurative speech, rich variety, easy language and lively comparisons, but also a spirit that enkindles fire, zeal, and life in the reader

4) Never attempt to compose a hymn till they feel their souls near to heaven, under the influence of the Holy Spirit and then the Spirit will be ready to bless his work.

William wrote with a degree of inspiration that has always characterised the work of the most gifted poets. Many verses ‘came’ to him in the dead of night, and so he always went to bed prepared with pen, ink and a board on which to rest his paper. As he lay musing on the profound truths of the Christian life, the thoughts would begin to burn themselves into his mind. Sometimes in the early hours of the morning he would suddenly cry out, ‘O bring light, my vessel is running over!’ Then he would write down the words racing through his brain.

Iain Murray records an incident in the life of Dr Martyn Lloyd Jones which shows how the hymns of William Williams were used of God to revive the soul with a deep powerful impression of the majesty and mercy of God….

In the summer of 1949, while on holiday in North Wales the doctor had retired early on Saturday evening Alone he was reading the Welsh hymns of William Williams in the Calvinistic Methodist hymn book when he was given such a consciousness of the presence and love of God as seemed to excel all that he had ever known before. It was a foretaste of glory.’ This was the reason why at a conference for Christian Ministers Lloyd Jones could say that William’s hymns ‘have an incomparable blend of truly great poetry and perfect theology.’

Let’s look at a few of William William’s hymns, one of my favourites is:-

Jesus, Jesus, all sufficient,

beyond telling is Thy worth;

In Thy Name lie greater treasures

than the richest found on earth.

Such abundance,

Is my portion with my God

~~~~

In Thy gracious face there’s beauty

Far surpassing every thing

Found in all the earth’s great wonders

Mortal eye hath ever seen.

Rose of Sharon

Thou Thyself art heaven’s delight

Written originally in Welsh it was later translated into English. William’s here expresses almost it seems with wonder – such abundance is my portion. He goes on to describe Christ’s beauty as the Rose of Sharon the most beautiful of flowers and indeed heaven’s delight

Many hymns display this blend, one such lesser known hymn, translated into English by Robert Maynard Jones:-

In Eden – sad indeed that day-

My countless blessings fled away,

My crown fell in disgrace.

But on victorious Calvary

That crown was won again for me –

My life shall all be praise.

Faith, see the place, and see the tree

Where heaven’s Prince, instead of me,

Was nailed to bear my shame.

Bruised was the dragon by the Son,

Though two had wounds, there conquered One –

And Jesus was His name.

This hymn encompasses the sovereignty of God from all eternity, the total depravity of man, the victory of the cross over Satan, the wonder of saving faith and the crown which those saved by grace will receive in glory.

William Williams drew much of his imagery from the natural world around him. As he travelled among the rugged mountains across barren tracts of land and beside the rivers that flowed through the valleys he would see comparisons that gave him substance for his verses.

William used the landscape of his native Brecon Beacons vividly in many of his hymns, in another of William’s hymns again translated into English by Robert Maynard Jones he describes the Christian life as a pilgrimage.

A pilgrim in a desert land,

I wander far and wide,

Expecting I may sometime come

Close to my fathers side.

Ahead of me I think I hear

Sounds of a heavenly choir,

A conquering host already gone

Through tempest flood and fire.

Come Holy Spirit, fire by night

Pillar of cloud by day:

Lead for I dare not take a step

Unless Thou show the way.

So prone am I when on my own

To stray from side to side

I need each step to Paradise

My God to be my guide.

I have a yearning for that land

Where the unnumbered throng

Extol the death on Calvary

In heaven’s unending song.

Did the sound of bird songs as he journeyed remind him of the heavenly choir mentioned in verse 5 who sing the praises of Christ’s atoning sacrifice?

Dangers were ever present as any climber in the Welsh mountains knows.

We wouldn’t be complete unless we looked at his most famous of hymns, written in 1745 for the second book of Alleluia. – Guide me O Thou great Jehovah.

Originally it had 5 x 6 line verses, and was first translated into English in 1772.

Guide me O Thou great Jehovah,

Pilgrim through this barren land;

I am weak, but Thou art mighty,

Hold me with Thy powerful hand

Bread of Heaven,

Feed me till I want no more

~~~~

Open Thou the crystal fountain

Whence the healing stream doth flow;

Let the fiery, cloudy pillar

Lead me all my journey through;

Strong Deliverer

Be Thou still my strength and shield.

~~~~

When I tread the verge of Jordan,

Bid my anxious fears subside;

Death of death and hell’s destruction,

Land me safe on Canaan’s side;

Songs of praises

I will ever give to thee.

The imagery of the hymn is drawn from a number of events during the exodus of the Israelite’s on their journey to the promised land

The bread of heaven – manna

The crystal fountain – water from the rock

The fiery cloudy pillar – pillar of cloud and fire leading them through the wilderness

In his analysis of Christian Hymns, Cliff Knight describes the hymn like this…. “This hymn based on the journey of Israel through the wilderness, is no doubt inspired by Williams own travels up and down Wales as he journeyed on horseback over 2,000 miles a year, often suffering cruel opposition and physical violence.”

Although the hymn is based on history it has a message for the Christian today as he journeys through life. There are many times when life seems hard and times when in weakness, the Christian calls on the mighty God to sustain him with His powerful hand. Food and guidance are His daily provision until we reach Canaan’s side.

In our lives as believers, which can be very perplexing at times, I trust that this will be our daily prayer “Guide me O thou Great Jehovah – I am weak but thou are mighty, hold me with thy powerful hand

May we all have our eyes fixed on Canaan where we will all sing Songs of praise.

These are just a few of William William’s hymns which we are able to enjoy.

As well as giving voice to our praise and worship of almighty God as congregations of God’s people, these hymns of William William’s can also be very helpful in our private devotions, enabling us to focus on the doctrines of grace.

From his birth in an isolated farmhouse deep in the Brecon Beacons, to his hymns still being sung nearly 300 years later across the world, This is the life and work of William Williams Pantycelyn – The sweet singer of Wales.

Acknowledgements

William Williams and Welsh Calvinistic Methodism – Paper by Dr Martyn Lloyd Jones for the 1968 Westminster Conference.

William Williams Pantycelyn by Rev. Sam Thomas

William Williams Pantycelyn by Iestyn Roberts.

Bread of Heaven by Eifion Evans.

Fire in the Thatch by Eifion Evans

Our hymn writers and their hymns by Faith Cook.

A companion to Christian Hymns by Cliff Knight.